Tanabe

started his career by erecting monumental sculptures in public squares (in Saku,

Naoetsu, and Yokohama), but later he began making art based on a worldview that

is common to most of the peoples of Asia, the idea that "a single grain of

rice is as heavy as Mt. Sumer," the high mountain at the center of the world.

His major works are monumental depictions of unhulled grains of wild rice (

momi)

made of stainless steel. One of these is included in the present exhibition. It

is meant to promote in-situ conservation of wild rice habitat. Similar works have

been accepted by the International Rice Research Institute in Manila as well as

museums, schools, and government institutions in Japan, Korea, China, Thailand,

India, the United States, Cuba, and Australia.

Wild

rice still grows today in the tropical regions of Asia in spite of the violent

effects of development; it is the source of the cultivated rice that has spread

throughout Asia and the rest of the world. It is the origin of rice cultivation,

a witness to the history of its advance. The original meaning of the word culture

is the cultivation of plants, wild rice corresponds to an ideal form of what later

became cultivated rice. If the ideal of a thing is lost, it will eventually be

destroyed. The survival of wild rice is connected to the fate of culture. Because

of Tanabeユs approach to his work, he notices the way of life of the people of

the rice terraces, the people who cultivate rice under the most extreme conditions.

There is deep meaning in collecting and preserving objects that were created there

over many generations. Tanabe has visited the remote villages of the Ifugao people

of Luzon twice under of the auspices of the IRRI, staying in ordinary houses,

and carefully observing the agricultural practices and life of these people who

live in harmony with nature.

In

the field of art, the tendency of positively evaluating artistic expressions of

ages and regions that exist outside of the tradition of Western art going back

to the renaissance is known as primitivism. From the late nineteenth century through

the twentieth century, there have been people who sought the source of beauty

in art tendency of thought has sought the source of beauty in art among the native

peoples of Africa, Oceania, and North America. This way of thinking has made a

revolutionary contribution to contemporary art. A new national museum being constructed

in France is acquiring objects made by the rice-growing peoples of Asia for its

collection. The poster announcing this future exhibition shows an image of the

rice god of the Ifugao like the one that appears in this exhibition.

Tanabe

says of his own collection,

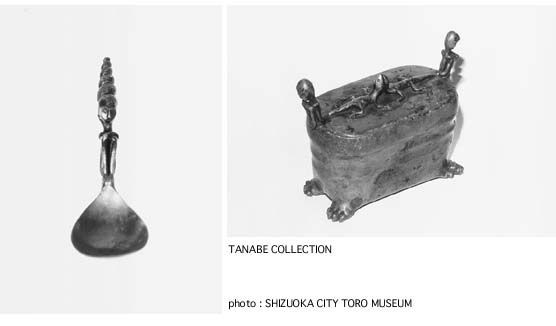

| These

many objects, rooted in the life of agricultural people, bring us an intense light

from a farming culture. Instead of "art" they show us the profound nature

of "survival." |

In the crisis of survival of the

present age, we can only hope that the Spoon with Carved Centipede (one of the

objects displayed in this exhibition), which was made long ago by the people of

the rice terraces, can deliver the bitter medicine that we need to our mouths.