Ur

is a German prefix meaning original or primal. Goethe attached it to the word

for plant to create a new concept, Urpflanze, the original form

of a plant. The poet used this coined word to refer to the ideal form that serves

as a type or root of the plant that currently exists, a basic form that is susceptible

to various transformations. I have already explained the circumstances by which

Tanabe's work moved toward such an ur-condition in his search for the origins

of the path of rice cultivation. I look forward to seeing the results of his explorations

in this exhibition. Ur

is a German prefix meaning original or primal. Goethe attached it to the word

for plant to create a new concept, Urpflanze, the original form

of a plant. The poet used this coined word to refer to the ideal form that serves

as a type or root of the plant that currently exists, a basic form that is susceptible

to various transformations. I have already explained the circumstances by which

Tanabe's work moved toward such an ur-condition in his search for the origins

of the path of rice cultivation. I look forward to seeing the results of his explorations

in this exhibition.

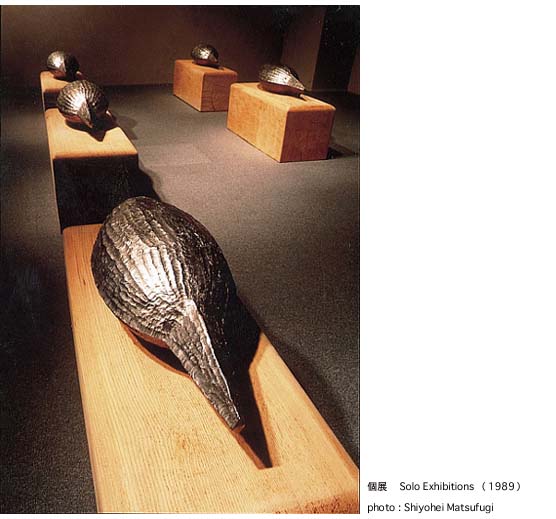

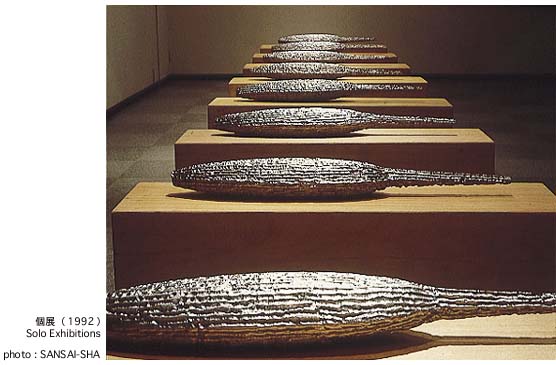

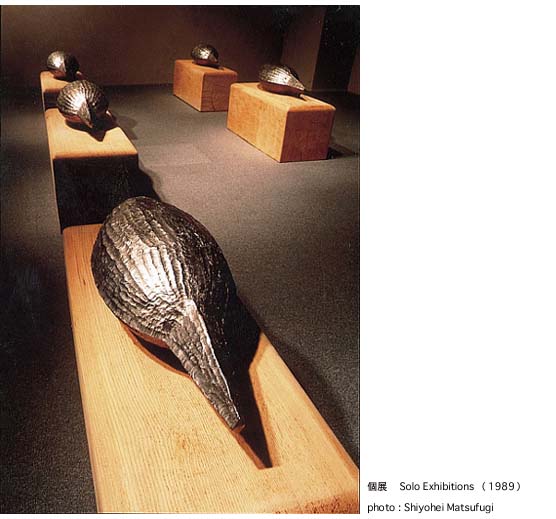

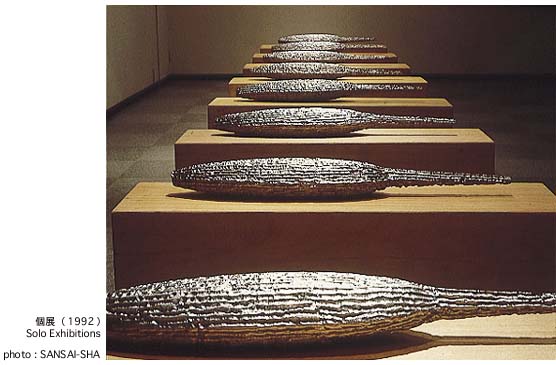

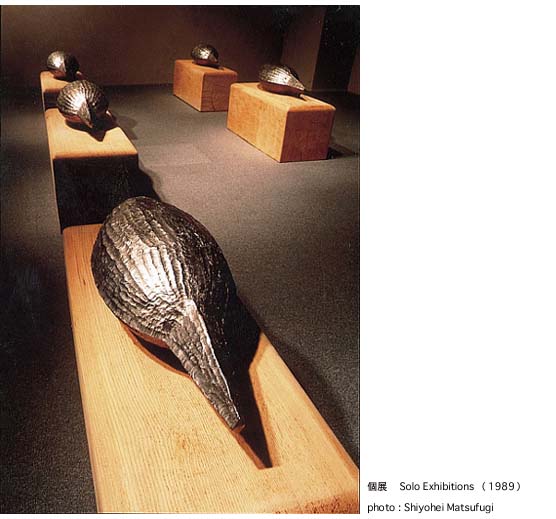

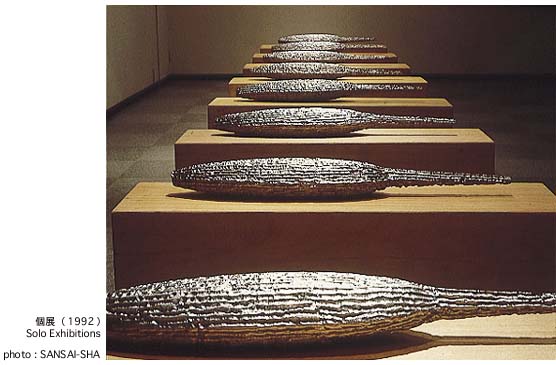

A "hundred

flowers are blooming" in the scientific research related to the path of rice

cultivation. Wild rice grains have been found in archaeological excavations in

the Yangtze River drainage, which has some of the oldest remains of rice cultivation

in the world. There has been a remarkable find at the He Me Du site of momi

that is more than 7000 years old. Tanabe has made a serious study to increase

his knowledge of rice cultivation and created many works of all sizes on the theme

of momi. Work from this series of cast stainless steel sculptures

was shown in solo exhibitions in 1989 and 1992. There were dramatic changes in

form during that period, from the smooth, round form of a grain of cultivated

rice to the irregular form of a piece of wild rice with a long protuberance, the

nogi. A "hundred

flowers are blooming" in the scientific research related to the path of rice

cultivation. Wild rice grains have been found in archaeological excavations in

the Yangtze River drainage, which has some of the oldest remains of rice cultivation

in the world. There has been a remarkable find at the He Me Du site of momi

that is more than 7000 years old. Tanabe has made a serious study to increase

his knowledge of rice cultivation and created many works of all sizes on the theme

of momi. Work from this series of cast stainless steel sculptures

was shown in solo exhibitions in 1989 and 1992. There were dramatic changes in

form during that period, from the smooth, round form of a grain of cultivated

rice to the irregular form of a piece of wild rice with a long protuberance, the

nogi. |

|

Tanabe's

search took him deep into the untracked territory of wild rice. In ancient times,

wild rice crossed the line of 30 degrees north latitude and was eventually cultivated

in the north. This fact is known from the high proportion of wild rice among the

rice grains found at the He Me Du. Because of later temperature changes, wild

rice moved southward to tropical regions. As new strains of cultivated rice were

created, wild rice was treated as a weed when it sprouted in rice paddies, but

it eventually found a safe haven in marshy wilderness areas. No one knows who

began cultivating this wild rice over 7000 years ago. Of course, efforts were

made in modern times to preserve wild rice in gene banks and grow it in research

facilities, but it was quickly becoming extinct in its natural habitat because

of overdevelopment. In 1992, Tanabe met Dr. Yoichiro Sato, a distinguished researcher

in this field, and joined his movement to preserve the natural habitat of wild

rice. Tanabe's

search took him deep into the untracked territory of wild rice. In ancient times,

wild rice crossed the line of 30 degrees north latitude and was eventually cultivated

in the north. This fact is known from the high proportion of wild rice among the

rice grains found at the He Me Du. Because of later temperature changes, wild

rice moved southward to tropical regions. As new strains of cultivated rice were

created, wild rice was treated as a weed when it sprouted in rice paddies, but

it eventually found a safe haven in marshy wilderness areas. No one knows who

began cultivating this wild rice over 7000 years ago. Of course, efforts were

made in modern times to preserve wild rice in gene banks and grow it in research

facilities, but it was quickly becoming extinct in its natural habitat because

of overdevelopment. In 1992, Tanabe met Dr. Yoichiro Sato, a distinguished researcher

in this field, and joined his movement to preserve the natural habitat of wild

rice.

The series of sculptures

Tanabe created during this period were exhibited at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum

and He Me Du Ruins Museum in China and the International Rice Research Institute

(IRRI) in Manila, and these institutions purchased his work after the exhibitions

were over. The installation shown at the IRRI exhibition consisted of a silver-colored

cast stainless steel sculpture enshrined on a golden pile of momi

in an open burlap rice bag. It clearly conveyed the message that wild rice is

the father of cultivated rice, an irreplaceable jewel that is essential to the

future of humankind. The series of sculptures

Tanabe created during this period were exhibited at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum

and He Me Du Ruins Museum in China and the International Rice Research Institute

(IRRI) in Manila, and these institutions purchased his work after the exhibitions

were over. The installation shown at the IRRI exhibition consisted of a silver-colored

cast stainless steel sculpture enshrined on a golden pile of momi

in an open burlap rice bag. It clearly conveyed the message that wild rice is

the father of cultivated rice, an irreplaceable jewel that is essential to the

future of humankind.

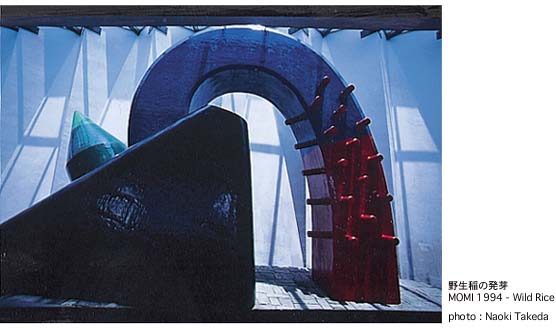

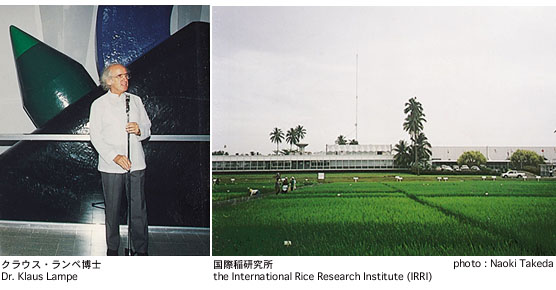

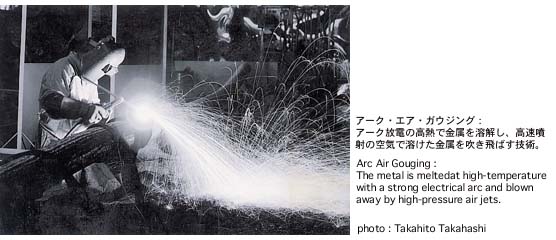

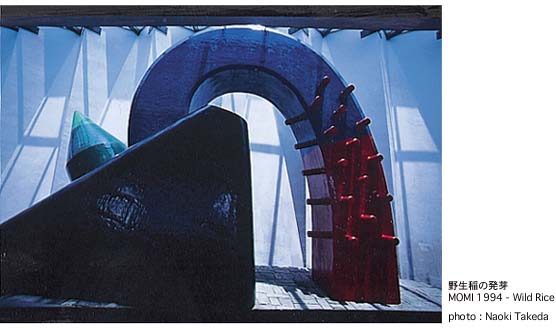

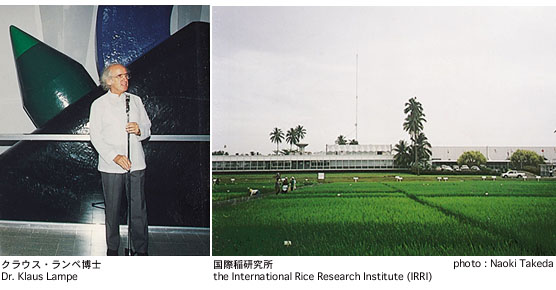

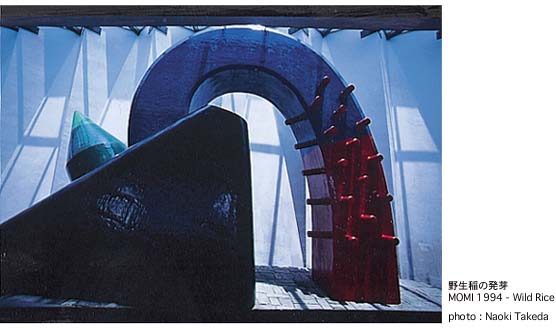

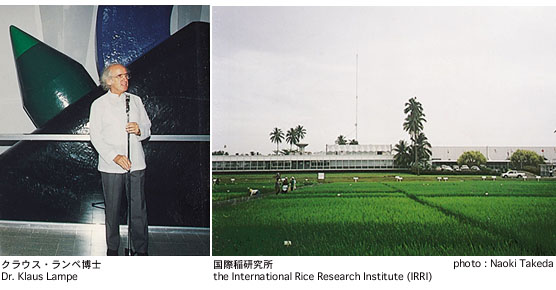

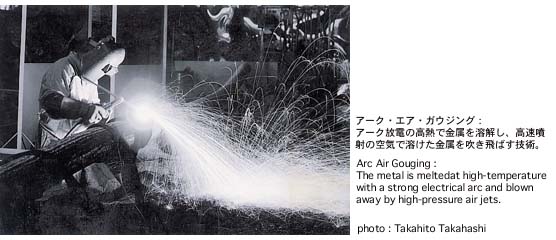

As demonstrated

by the exhibition at IRRI, Dr. Klaus Lampe, the German director general of the

institute at the time, understood the great importance of Tanabe's work. Dr. Lampe

invited Tanabe to the institute in 1994 commissioned him to make a freely designed

artwork for the observation hall, and the artist received the highest level of

wages paid to employees of the institute in spite of a difficult economic situation.

The doctor probably hoped to use this artwork to create a more open atmosphere

at the institute, to introduce a fresh spirit into the "ivory tower"

and give it the vitality it needed to continue its work into the future. In response

to this request, Tanabe used eight tons of red lauan wood to make MOMI 1994

- Wild Rice, a monumental work that held out a dream for the future. As demonstrated

by the exhibition at IRRI, Dr. Klaus Lampe, the German director general of the

institute at the time, understood the great importance of Tanabe's work. Dr. Lampe

invited Tanabe to the institute in 1994 commissioned him to make a freely designed

artwork for the observation hall, and the artist received the highest level of

wages paid to employees of the institute in spite of a difficult economic situation.

The doctor probably hoped to use this artwork to create a more open atmosphere

at the institute, to introduce a fresh spirit into the "ivory tower"

and give it the vitality it needed to continue its work into the future. In response

to this request, Tanabe used eight tons of red lauan wood to make MOMI 1994

- Wild Rice, a monumental work that held out a dream for the future. |

|

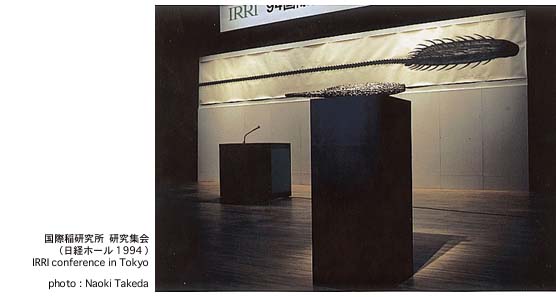

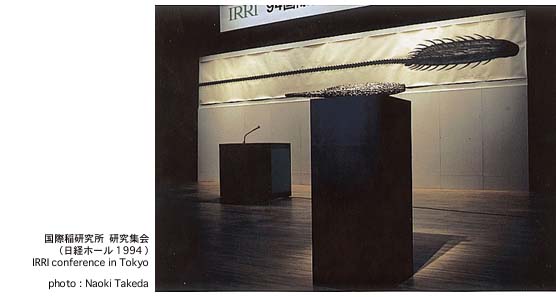

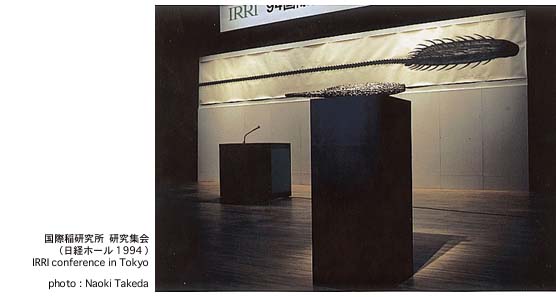

During

the same year, an IRRI conference was held in Tokyo, and Dr. Lampe asked Tanabe

to create artwork for the conference venue, Nikkei Hall. He made a large drawing

of a momi grain 11 meters long, displaying it in the center of the

stage with cast forms of momi on both sides of the podium as well

as an actual plow once used in the Philippines. In the entrance to the hall, he

displayed a large color photograph of MOMI 1994 - Wild Rice, which

he had just installed at IRRI headquarters. It was a display that expressed the

importance of returning to the source. Through the general consent of the participants

and Tanabe's own decision, the drawing and cast sculptures were donated to the

royal princess of Thailand, who sponsored the conference as well as presenting

a paper. During

the same year, an IRRI conference was held in Tokyo, and Dr. Lampe asked Tanabe

to create artwork for the conference venue, Nikkei Hall. He made a large drawing

of a momi grain 11 meters long, displaying it in the center of the

stage with cast forms of momi on both sides of the podium as well

as an actual plow once used in the Philippines. In the entrance to the hall, he

displayed a large color photograph of MOMI 1994 - Wild Rice, which

he had just installed at IRRI headquarters. It was a display that expressed the

importance of returning to the source. Through the general consent of the participants

and Tanabe's own decision, the drawing and cast sculptures were donated to the

royal princess of Thailand, who sponsored the conference as well as presenting

a paper. |

|

Right

after this meeting, the "Wild Rice Habitat Preservation" project was

initiated by the royal house of Thailand. Tanabe participated in this project

and, in 1997, installed a gigantic outdoor monument to wild rice, 33 meters in

length, at the Pathum Thani Rice Research Center. In this work, the main body

of the momi is three meters long, and the remaining 30 meters are

the nogi, the extended whisker, which is a minimum of ten times

the length of the grain. Right

after this meeting, the "Wild Rice Habitat Preservation" project was

initiated by the royal house of Thailand. Tanabe participated in this project

and, in 1997, installed a gigantic outdoor monument to wild rice, 33 meters in

length, at the Pathum Thani Rice Research Center. In this work, the main body

of the momi is three meters long, and the remaining 30 meters are

the nogi, the extended whisker, which is a minimum of ten times

the length of the grain. |

|

I

attended the unveiling ceremony of this monument. It reminded me in its overall

form of the unhulled ears of wild rice that I first saw at the National Genetic

Research Institute in Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture, which I visited with Tanabe

ten years ago. The body of the rice ear is filled with a life force that keeps

it alive for many years, and the nogi that extends from it has a

sensitive and elegant form. This is the subject that Tanabe has chosen for his

art. It is based on an idealistic concept of respect and praise for ancient ways

and artistic form. Tanabe refused to display this work in the front entrance because

he wanted to place it in the experimental rice paddies spreading around the center.

It was a remarkable achievement. The momi was revealed in the sunlight

after the veil was removed, singing out its idealistic message in a way that made

the entire site, all 160 hectares of space, fall silent. I

attended the unveiling ceremony of this monument. It reminded me in its overall

form of the unhulled ears of wild rice that I first saw at the National Genetic

Research Institute in Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture, which I visited with Tanabe

ten years ago. The body of the rice ear is filled with a life force that keeps

it alive for many years, and the nogi that extends from it has a

sensitive and elegant form. This is the subject that Tanabe has chosen for his

art. It is based on an idealistic concept of respect and praise for ancient ways

and artistic form. Tanabe refused to display this work in the front entrance because

he wanted to place it in the experimental rice paddies spreading around the center.

It was a remarkable achievement. The momi was revealed in the sunlight

after the veil was removed, singing out its idealistic message in a way that made

the entire site, all 160 hectares of space, fall silent. |

|