By YOKO

HANI

By YOKO

HANI

Staff writer

Artist Mitsuaki Tanabe is stubborn.

In the past 20 years, he has been creating sculptures themed on a single

motif: a grain of rice.

But the rice that Tanabe selects to sculpt is not the common-or-garden

sort that people normally stuff themselves with. Oh no, it is the "mother

of all rice" ― the wild variety that's the ancestor of today's cultivated

rice, and which is believed to have been sprouting on this planet for

no less than 10,000 years.

Since he started his wild-rice sculpting, Tanabe has consistently created

his artworks ― some huge; others detailed drawings of the aquatic grass's

seeds ― to highlight the herbiferous heritage of this key nutritional

resource whose mainly Asian habitats are now, experts say, threatened

by economic development.

"When I encountered 'wild rice' 20 years ago, I was inspired immensely

as an artist," says Yokohama-based Tanabe. "I learned from scientists

about wild rice and its habitats, and I wanted to do what I could to make

the situation better. I wanted to create artworks to make a strong visual

impact on people and lead them into learning about the importance of biodiversity."

After 20 years of effort, Tanabe's project took a mighty leap forward

recently when a United Nations food agency selected his sculpture of a

wild-rice seed for permanent display at its office.

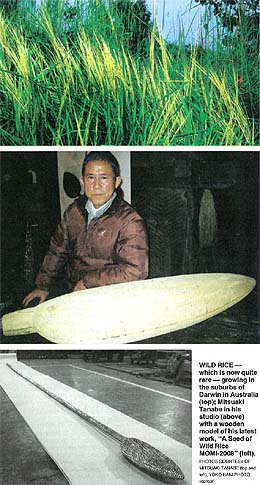

Then, on April 1, his latest work, "A Seed of Wild Rice MOMI-2008," was

installed by the Global Crop Diversity Trust at its headquarters in the

U.N.'s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) building in Rome, where

the trust will permanently display it in its entrance hall to commemorate

the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in which it is involved with the Norwegian

government and the Nordic Gene Bank.

As well as conserving currently threatened plant life, the vault is also a resource from which agricultural production at the regional or global level could be restarted in the event of natural or man-made disasters, according to the trust.

Tanabe's stainless-steel sculpture of an unhulled rice seed is 9 meters long, including a spearlike whisker extending from its tip ― a feature peculiar to wild rice. Weighing about 250 kg, the work was completed last December (with funding from several Japanese companies), and was shipped to Italy to be donated to the trust.

"This was absolutely a big event in my career. I never thought that my work might be installed in such an institution as a symbol of their activities for biodiversity," Tanabe says. "I feel so excited, as if I have been given a big prize as an artist."

But Tanabe, 69, was not an environmental artist from the beginning.

Born in 1939 in Tokyo's neighboring Kanagawa Prefecture, in 1961 he graduated from the sculpture department of Tama University of Arts in Tokyo. Then, during the first 15 years after graduating, he spent a lot of time studying alone and searching for his artistic inspiration ― sometimes by traveling to faraway countries. It was then that he met Isamu Noguchi, a prominent American sculptor, and Tanabe says that that meeting in Tokyo when Noguchi was visiting had a great influence on him.

Since the late 1970s, however, Tanabe has constantly created nature-based sculptures in which it is clear to see the roots of his current works. One example is a 40-meter-high structure titled "SAKU" (the name of a city in Nagano Prefecture) that was installed in the garden of the Saku Municipal Museum of Modern Arts for its opening in 1983.

The germ of this unusual creation came to Tanabe when he visited the planned site for the museum. There, he noticed that the prevailing wind seemed to be from the north. Intrigued, he checked the Meteorological Agency data and found that in the two previous years it had blown from either the east- northeast or the north-northeast on about 300 days a year.

That data gave him his inspiration to create a sculpture with a theme of "wind from the north."

"I wanted to make the artwork to catch the wind from the north and bring it down to meet people," Tanabe said, recollecting his thoughts behind the work.

What he finally sculpted was a 40-meter-high stainless-steel pole adjoining a purpose-built structure on the ground. The top of the pole has a bulblike pod about 2 meters across with window-like holes on the sides through which the wind blows and is then channeled down the hollow pole to the structure on the ground.

"It was extremely difficult to design the system to bring the wind down. I sought advice from experts in hydrodynamics, meteorology, air currents and wind-power generation," Tanabe says. "But it was fascinating. On the ground, I could see things that were brought along on the wind ― insects and seeds among them."

It was a few years after his "SAKU" work that Tanabe says he encountered wild rice ― but it was one of those chance encounters that can change a life; in his case by giving him the theme of bio- diversity that he has pursued ever since.

"When I was looking for a motif, I happened to read a book on wild rice. I knew the importance of biodiversity, but I was shocked when I learned how difficult it is to conserve the habitats of wild rice in the reality of economic development," he says.

Soon after

reading the book, he contacted one of the two academics mentioned there,

who recommended that he should visit the National Institute of Genetics

in Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture. There, he says he had another tremendous

shock when he saw wild rice being cultivated for research purposes.

Soon after

reading the book, he contacted one of the two academics mentioned there,

who recommended that he should visit the National Institute of Genetics

in Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture. There, he says he had another tremendous

shock when he saw wild rice being cultivated for research purposes."The wild rice plants looked so different from those I was familiar with. They have a long whisker and thornlike projections on the surface of the grains. I heard that sparrows cannot pick out the seeds because of those projections."

After that, the more he learned about wild rice the more deeply he became involved with it. This led to Tanabe visiting habitats of wild rice in Asian countries, including Thailand and India, to deepen his understanding.

Now he is so knowledgeable that he sounds like a biodiversity expert.

"There are two approaches to protecting biodiversity. One is to create institutions such as gene banks and preserve seeds there. The other is to conserve the habitats. But it is not easy."

Since the 1990s, Tanabe has been more involved in the conservation movement through, among other things, meeting both Japanese and foreign agricultural experts. As a result, his network of experts has progressively grown, and in 1994 he was invited over by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines as an environmental artist, and there he spent four months creating a wild-rice-seed sculpture titled "MOMI-1994 Wild Rice."

Then, at the first International Conference on Wild Rice in 2002 in Katmandu, a drawing by Tanabe of a single shoot of wild rice ― 9 meters long and 1.3 meters wide ― was put on display and attracted great attention.

After that came the commission from the Global Crop Diversity Trust in Rome, to whom he donated his latest sculpture of a seed of wild rice.

"It is meaningless if the sculptures do not have power as art," he says.

Perhaps paradoxically, Tanabe created his latest work, "A Seed of Wild Rice MOMI-2008," out of stainless steel. He says he wanted to express his art using a material symbolizing the 20th century.

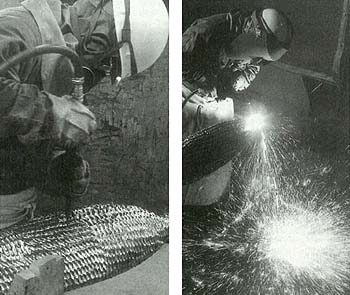

After designing a wooden model at his studio in Yokohama, he says the casting and sculpting at a factory in Niigata Prefecture took about three months. That creative process involved melting and gouging the surface of the sculpture using an electrical arc discharge operating at about 3,000 degrees.

According to Taro Nomura, an art critic, that technique, known as "arc-air gouging," requires very high skills. He explained in a leaflet describing Tanabe's latest work that engineers are reluctant to use the technique, "because it can easily destroy the work if you just make a tiny technical error."

"The application of this technique is unique to Tanabe. He is the only person who can handle it," Nomura says.

Talking about the social meaning of Tanabe's work, Julian Laird, the director of development and communications for the Global Crop Diversity Trust, commented by e-mail that Tanabe's sculpture gives opportunities "to portray a crop in a way that makes people stop and think."

"Crop diversity is a subject with which people are familiar on a subconscious level ― we all buy, cook and eat different varieties of different crops," he said. "But we do not necessarily think about how so many varieties exist, or why. Crop diversity is one of our most important natural resources ― but it is in danger because it is poorly appreciated and taken for granted.

"That is a sculpture of a seed of wild rice, but it does not look as people would expect it to. A work of art that makes people think again about something they thought they knew well (such as a grain of rice) can therefore reinforce the trust's message," he said.

For his part, Tanabe sees this recent event in Rome as having given him a clue to answer some of the weighty questions that creators always ask themselves.

"Artists often have to question 'why do I create my works?' " he says. "It's often a hard one to answer. But this time, I felt I could perform a wider duty as an artist through my work ― and I feel very happy."